480 lines

18 KiB

Markdown

480 lines

18 KiB

Markdown

# 2.2 Go foundation

|

||

|

||

In this section, we are going to teach you how to define constants, variables with elementary types and some skills in Go programming.

|

||

|

||

## Define variables

|

||

|

||

There are many forms of syntax that can be used to define variables in Go.

|

||

|

||

The keyword `var` is the basic form to define variables, notice that Go puts the variable type `after` the variable name.

|

||

```Go

|

||

// define a variable with name “variableName” and type "type"

|

||

var variableName type

|

||

```

|

||

Define multiple variables.

|

||

```Go

|

||

// define three variables which types are "type"

|

||

var vname1, vname2, vname3 type

|

||

```

|

||

Define a variable with initial value.

|

||

```Go

|

||

// define a variable with name “variableName”, type "type" and value "value"

|

||

var variableName type = value

|

||

```

|

||

Define multiple variables with initial values.

|

||

```Go

|

||

/*

|

||

Define three variables with type "type", and initialize their values.

|

||

vname1 is v1, vname2 is v2, vname3 is v3

|

||

*/

|

||

var vname1, vname2, vname3 type = v1, v2, v3

|

||

```

|

||

Do you think that it's too tedious to define variables use the way above? Don't worry, because the Go team has also found

|

||

this to be a problem. Therefore if you want to define variables with initial values, we can just omit the variable type,

|

||

so the code will look like this instead:

|

||

```Go

|

||

/*

|

||

Define three variables without type "type", and initialize their values.

|

||

vname1 is v1,vname2 is v2,vname3 is v3

|

||

*/

|

||

var vname1, vname2, vname3 = v1, v2, v3

|

||

```

|

||

Well, I know this is still not simple enough for you. Let's see how we fix it.

|

||

```Go

|

||

/*

|

||

Define three variables without type "type" and without keyword "var", and initialize their values.

|

||

vname1 is v1,vname2 is v2,vname3 is v3

|

||

*/

|

||

vname1, vname2, vname3 := v1, v2, v3

|

||

```

|

||

Now it looks much better. Use `:=` to replace `var` and `type`, this is called a **short assignment**. It has one limitation: this form can only be used inside of a functions. You will get compile errors if you try to use it outside of function bodies. Therefore, we usually use `var` to define global variables.

|

||

|

||

`_` (blank) is a special variable name. Any value that is given to it will be ignored. For example, we give `35` to `b`, and discard `34`.( ***This example just show you how it works. It looks useless here because we often use this symbol when we get function return values.*** )

|

||

```Go

|

||

_, b := 34, 35

|

||

```

|

||

If you don't use variables that you've defined in your program, the compiler will give you compilation errors. Try to compile the following code and see what happens.

|

||

```Go

|

||

package main

|

||

|

||

func main() {

|

||

var i int

|

||

}

|

||

```

|

||

## Constants

|

||

|

||

So-called constants are the values that are determined during compile time and you cannot change them during runtime. In Go, you can use number, boolean or string as types of constants.

|

||

|

||

Define constants as follows.

|

||

```Go

|

||

const constantName = value

|

||

// you can assign type of constants if it's necessary

|

||

const Pi float32 = 3.1415926

|

||

```

|

||

More examples.

|

||

```Go

|

||

const Pi = 3.1415926

|

||

const i = 10000

|

||

const MaxThread = 10

|

||

const prefix = "astaxie_"

|

||

```

|

||

## Elementary types

|

||

|

||

### Boolean

|

||

|

||

In Go, we use `bool` to define a variable as boolean type, the value can only be `true` or `false`, and `false` will be the default value. ( ***You cannot convert variables' type between number and boolean!*** )

|

||

```Go

|

||

// sample code

|

||

var isActive bool // global variable

|

||

var enabled, disabled = true, false // omit type of variables

|

||

|

||

func test() {

|

||

var available bool // local variable

|

||

valid := false // brief statement of variable

|

||

available = true // assign value to variable

|

||

}

|

||

```

|

||

### Numerical types

|

||

|

||

Integer types include both signed and unsigned integer types. Go has `int` and `uint` at the same time, they have same length, but specific length depends on your operating system. They use 32-bit in 32-bit operating systems, and 64-bit in 64-bit operating systems. Go also has types that have specific length including `rune`, `int8`, `int16`, `int32`, `int64`, `byte`, `uint8`, `uint16`, `uint32`, `uint64`. Note that `rune` is alias of `int32` and `byte` is alias of `uint8`.

|

||

|

||

One important thing you should know that you cannot assign values between these types, this operation will cause compile errors.

|

||

```Go

|

||

var a int8

|

||

|

||

var b int32

|

||

|

||

c := a + b

|

||

```

|

||

Although int32 has a longer length than int8, and has the same type as int, you cannot assign values between them. ( ***c will be asserted as type `int` here*** )

|

||

|

||

Float types have the `float32` and `float64` types and no type called `float`. The latter one is the default type if using brief statement.

|

||

|

||

That's all? No! Go supports complex numbers as well. `complex128` (with a 64-bit real and 64-bit imaginary part) is the default type, if you need a smaller type, there is one called `complex64` (with a 32-bit real and 32-bit imaginary part). Its form is `RE+IMi`, where `RE` is real part and `IM` is imaginary part, the last `i` is the imaginary number. There is a example of complex number.

|

||

```Go

|

||

var c complex64 = 5+5i

|

||

//output: (5+5i)

|

||

fmt.Printf("Value is: %v", c)

|

||

```

|

||

### String

|

||

|

||

We just talked about how Go uses the UTF-8 character set. Strings are represented by double quotes `""` or backticks ``` `` ```.

|

||

```Go

|

||

// sample code

|

||

var frenchHello string // basic form to define string

|

||

var emptyString string = "" // define a string with empty string

|

||

func test() {

|

||

no, yes, maybe := "no", "yes", "maybe" // brief statement

|

||

japaneseHello := "Ohaiou"

|

||

frenchHello = "Bonjour" // basic form of assign values

|

||

}

|

||

```

|

||

It's impossible to change string values by index. You will get errors when you compile the following code.

|

||

```Go

|

||

var s string = "hello"

|

||

s[0] = 'c'

|

||

```

|

||

What if I really want to change just one character in a string? Try the following code.

|

||

```Go

|

||

s := "hello"

|

||

c := []byte(s) // convert string to []byte type

|

||

c[0] = 'c'

|

||

s2 := string(c) // convert back to string type

|

||

fmt.Printf("%s\n", s2)

|

||

```

|

||

You use the `+` operator to combine two strings.

|

||

```Go

|

||

s := "hello,"

|

||

m := " world"

|

||

a := s + m

|

||

fmt.Printf("%s\n", a)

|

||

```

|

||

and also.

|

||

```Go

|

||

s := "hello"

|

||

s = "c" + s[1:] // you cannot change string values by index, but you can get values instead.

|

||

fmt.Printf("%s\n", s)

|

||

```

|

||

What if I want to have a multiple-line string?

|

||

```Go

|

||

m := `hello

|

||

world`

|

||

```

|

||

``` ` ``` will not escape any characters in a string.

|

||

|

||

### Error types

|

||

|

||

Go has one `error` type for purpose of dealing with error messages. There is also a package called `errors` to handle errors.

|

||

```Go

|

||

err := errors.New("emit macho dwarf: elf header corrupted")

|

||

if err != nil {

|

||

fmt.Print(err)

|

||

}

|

||

```

|

||

### Underlying data structure

|

||

|

||

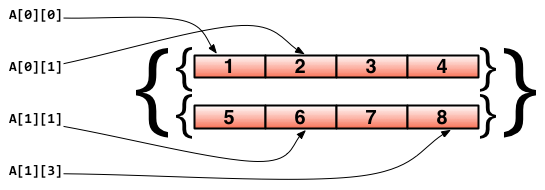

The following picture comes from an article about [Go data structure](http://research.swtch.com/godata) in [Russ Cox's Blog](http://research.swtch.com/). As you can see, Go utilizes blocks of memory to store data.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Figure 2.1 Go underlying data structure

|

||

|

||

## Some skills

|

||

|

||

### Define by group

|

||

|

||

If you want to define multiple constants, variables or import packages, you can use the group form.

|

||

|

||

Basic form.

|

||

```Go

|

||

import "fmt"

|

||

import "os"

|

||

|

||

const i = 100

|

||

const pi = 3.1415

|

||

const prefix = "Go_"

|

||

|

||

var i int

|

||

var pi float32

|

||

var prefix string

|

||

```

|

||

Group form.

|

||

```Go

|

||

import(

|

||

"fmt"

|

||

"os"

|

||

)

|

||

|

||

const(

|

||

i = 100

|

||

pi = 3.1415

|

||

prefix = "Go_"

|

||

)

|

||

|

||

var(

|

||

i int

|

||

pi float32

|

||

prefix string

|

||

)

|

||

```

|

||

Unless you assign the value of constant is `iota`, the first value of constant in the group `const()` will be `0`. If following constants don't assign values explicitly, their values will be the same as the last one. If the value of last constant is `iota`, the values of following constants which are not assigned are `iota` also.

|

||

|

||

### iota enumerate

|

||

|

||

Go has one keyword called `iota`, this keyword is to make `enum`, it begins with `0`, increased by `1`.

|

||

```Go

|

||

const(

|

||

x = iota // x == 0

|

||

y = iota // y == 1

|

||

z = iota // z == 2

|

||

w // If there is no expression after the constants name, it uses the last expression,

|

||

//so it's saying w = iota implicitly. Therefore w == 3, and y and z both can omit "= iota" as well.

|

||

)

|

||

|

||

const v = iota // once iota meets keyword `const`, it resets to `0`, so v = 0.

|

||

|

||

const (

|

||

e, f, g = iota, iota, iota // e=0,f=0,g=0 values of iota are same in one line.

|

||

)

|

||

```

|

||

### Some rules

|

||

|

||

The reason that Go is concise because it has some default behaviors.

|

||

|

||

- Any variable that begins with a capital letter means it will be exported, private otherwise.

|

||

- The same rule applies for functions and constants, no `public` or `private` keyword exists in Go.

|

||

|

||

## array, slice, map

|

||

|

||

### array

|

||

|

||

`array` is an array obviously, we define one as follows.

|

||

```Go

|

||

var arr [n]type

|

||

```

|

||

in `[n]type`, `n` is the length of the array, `type` is the type of its elements. Like other languages, we use `[]` to get or set element values within arrays.

|

||

```Go

|

||

var arr [10]int // an array of type [10]int

|

||

arr[0] = 42 // array is 0-based

|

||

arr[1] = 13 // assign value to element

|

||

fmt.Printf("The first element is %d\n", arr[0])

|

||

// get element value, it returns 42

|

||

fmt.Printf("The last element is %d\n", arr[9])

|

||

//it returns default value of 10th element in this array, which is 0 in this case.

|

||

```

|

||

Because length is a part of the array type, `[3]int` and `[4]int` are different types, so we cannot change the length of arrays. When you use arrays as arguments, functions get their copies instead of references! If you want to use references, you may want to use `slice`. We'll talk about later.

|

||

|

||

It's possible to use `:=` when you define arrays.

|

||

```Go

|

||

a := [3]int{1, 2, 3} // define an int array with 3 elements

|

||

|

||

b := [10]int{1, 2, 3}

|

||

// define a int array with 10 elements, of which the first three are assigned.

|

||

//The rest of them use the default value 0.

|

||

|

||

c := [...]int{4, 5, 6} // use `…` to replace the length parameter and Go will calculate it for you.

|

||

```

|

||

You may want to use arrays as arrays' elements. Let's see how to do this.

|

||

```Go

|

||

// define a two-dimensional array with 2 elements, and each element has 4 elements.

|

||

doubleArray := [2][4]int{[4]int{1, 2, 3, 4}, [4]int{5, 6, 7, 8}}

|

||

|

||

// The declaration can be written more concisely as follows.

|

||

easyArray := [2][4]int{{1, 2, 3, 4}, {5, 6, 7, 8}}

|

||

```

|

||

Array underlying data structure.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Figure 2.2 Multidimensional array mapping relationship

|

||

|

||

### slice

|

||

|

||

In many situations, the array type is not a good choice -for instance when we don't know how long the array will be when we define it. Thus, we need a "dynamic array". This is called `slice` in Go.

|

||

|

||

`slice` is not really a `dynamic array`. It's a reference type. `slice` points to an underlying `array` whose declaration is similar to `array`, but doesn't need length.

|

||

```Go

|

||

// just like defining an array, but this time, we exclude the length.

|

||

var fslice []int

|

||

```

|

||

Then we define a `slice`, and initialize its data.

|

||

```Go

|

||

slice := []byte {'a', 'b', 'c', 'd'}

|

||

```

|

||

`slice` can redefine existing slices or arrays. `slice` uses `array[i:j]` to slice, where `i` is

|

||

the start index and `j` is end index, but notice that `array[j]` will not be sliced since the length

|

||

of the slice is `j-i`.

|

||

```Go

|

||

// define an array with 10 elements whose types are bytes

|

||

var ar = [10]byte {'a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f', 'g', 'h', 'i', 'j'}

|

||

|

||

// define two slices with type []byte

|

||

var a, b []byte

|

||

|

||

// 'a' points to elements from 3rd to 5th in array ar.

|

||

a = ar[2:5]

|

||

// now 'a' has elements ar[2],ar[3] and ar[4]

|

||

|

||

// 'b' is another slice of array ar

|

||

b = ar[3:5]

|

||

// now 'b' has elements ar[3] and ar[4]

|

||

```

|

||

Notice the differences between `slice` and `array` when you define them. We use `[…]` to let Go

|

||

calculate length but use `[]` to define slice only.

|

||

|

||

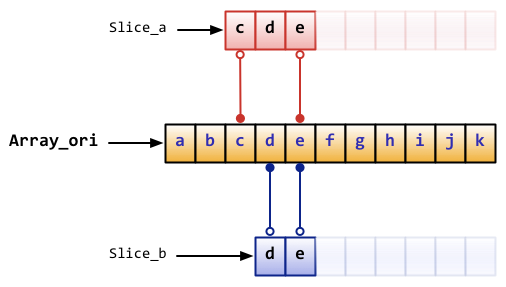

Their underlying data structure.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Figure 2.3 Correspondence between slice and array

|

||

|

||

slice has some convenient operations.

|

||

|

||

- `slice` is 0-based, `ar[:n]` equals to `ar[0:n]`

|

||

- The second index will be the length of `slice` if omitted, `ar[n:]` equals to `ar[n:len(ar)]`.

|

||

- You can use `ar[:]` to slice whole array, reasons are explained in first two statements.

|

||

|

||

More examples pertaining to `slice`

|

||

```Go

|

||

// define an array

|

||

var array = [10]byte{'a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f', 'g', 'h', 'i', 'j'}

|

||

// define two slices

|

||

var aSlice, bSlice []byte

|

||

|

||

// some convenient operations

|

||

aSlice = array[:3] // equals to aSlice = array[0:3] aSlice has elements a,b,c

|

||

aSlice = array[5:] // equals to aSlice = array[5:10] aSlice has elements f,g,h,i,j

|

||

aSlice = array[:] // equals to aSlice = array[0:10] aSlice has all elements

|

||

|

||

// slice from slice

|

||

aSlice = array[3:7] // aSlice has elements d,e,f,g,len=4,cap=7

|

||

bSlice = aSlice[1:3] // bSlice contains aSlice[1], aSlice[2], so it has elements e,f

|

||

bSlice = aSlice[:3] // bSlice contains aSlice[0], aSlice[1], aSlice[2], so it has d,e,f

|

||

bSlice = aSlice[0:5] // slice could be expanded in range of cap, now bSlice contains d,e,f,g,h

|

||

bSlice = aSlice[:] // bSlice has same elements as aSlice does, which are d,e,f,g

|

||

```

|

||

`slice` is a reference type, so any changes will affect other variables pointing to the same slice or array.

|

||

For instance, in the case of `aSlice` and `bSlice` above, if you change the value of an element in `aSlice`,

|

||

`bSlice` will be changed as well.

|

||

|

||

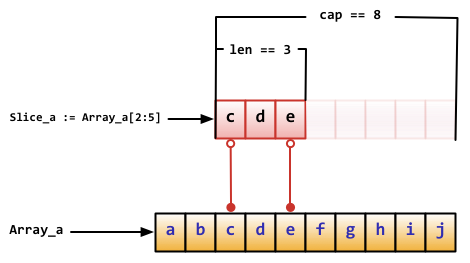

`slice` is like a struct by definition and it contains 3 parts.

|

||

|

||

- A pointer that points to where `slice` starts.

|

||

- The length of `slice`.

|

||

- Capacity, the length from start index to end index of `slice`.

|

||

```Go

|

||

Array_a := [10]byte{'a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f', 'g', 'h', 'i', 'j'}

|

||

Slice_a := Array_a[2:5]

|

||

```

|

||

The underlying data structure of the code above as follows.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Figure 2.4 Array information of slice

|

||

|

||

There are some built-in functions for slice.

|

||

|

||

- `len` gets the length of `slice`.

|

||

- `cap` gets the maximum length of `slice`

|

||

- `append` appends one or more elements to `slice`, and returns `slice` .

|

||

- `copy` copies elements from one slice to the other, and returns the number of elements that were copied.

|

||

|

||

Attention: `append` will change the array that `slice` points to, and affect other slices that point to the same array.

|

||

Also, if there is not enough length for the slice (`(cap-len) == 0`), `append` returns a new array for this slice. When

|

||

this happens, other slices pointing to the old array will not be affected.

|

||

|

||

### map

|

||

|

||

`map` behaves like a dictionary in Python. Use the form `map[keyType]valueType` to define it.

|

||

|

||

Let's see some code. The 'set' and 'get' values in `map` are similar to `slice`, however the index in `slice` can only be

|

||

of type 'int' while `map` can use much more than that: for example `int`, `string`, or whatever you want. Also, they are

|

||

all able to use `==` and `!=` to compare values.

|

||

```Go

|

||

// use string as the key type, int as the value type, and `make` initialize it.

|

||

var numbers map[string] int

|

||

// another way to define map

|

||

numbers := make(map[string]int)

|

||

numbers["one"] = 1 // assign value by key

|

||

numbers["ten"] = 10

|

||

numbers["three"] = 3

|

||

|

||

fmt.Println("The third number is: ", numbers["three"]) // get values

|

||

// It prints: The third number is: 3

|

||

```

|

||

Some notes when you use map.

|

||

|

||

- `map` is disorderly. Everytime you print `map` you will get different results. It's impossible to get values by `index` -you have to use `key`.

|

||

- `map` doesn't have a fixed length. It's a reference type just like `slice`.

|

||

- `len` works for `map` also. It returns how many `key`s that map has.

|

||

- It's quite easy to change the value through `map`. Simply use `numbers["one"]=11` to change the value of `key` one to `11`.

|

||

|

||

You can use form `key:val` to initialize map's values, and `map` has built-in methods to check if the `key` exists.

|

||

|

||

Use `delete` to delete an element in `map`.

|

||

```Go

|

||

// Initialize a map

|

||

rating := map[string]float32 {"C":5, "Go":4.5, "Python":4.5, "C++":2 }

|

||

// map has two return values. For the second return value, if the key doesn't

|

||

//exist,'ok' returns false. It returns true otherwise.

|

||

csharpRating, ok := rating["C#"]

|

||

if ok {

|

||

fmt.Println("C# is in the map and its rating is ", csharpRating)

|

||

} else {

|

||

fmt.Println("We have no rating associated with C# in the map")

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

delete(rating, "C") // delete element with key "c"

|

||

```

|

||

As I said above, `map` is a reference type. If two `map`s point to same underlying data,

|

||

any change will affect both of them.

|

||

```Go

|

||

m := make(map[string]string)

|

||

m["Hello"] = "Bonjour"

|

||

m1 := m

|

||

m1["Hello"] = "Salut" // now the value of m["hello"] is Salut

|

||

```

|

||

### make, new

|

||

|

||

`make` does memory allocation for built-in models, such as `map`, `slice`, and `channel`, while `new` is for types'

|

||

memory allocation.

|

||

|

||

`new(T)` allocates zero-value to type `T`'s memory, returns its memory address, which is the value of type `*T`. By Go's

|

||

definition, it returns a pointer which points to type `T`'s zero-value.

|

||

|

||

`new` returns pointers.

|

||

|

||

The built-in function `make(T, args)` has different purposes than `new(T)`. `make` can be used for `slice`, `map`,

|

||

and `channel`, and returns a type `T` with an initial value. The reason for doing this is because the underlying data of

|

||

these three types must be initialized before they point to them. For example, a `slice` contains a pointer that points to

|

||

the underlying `array`, length and capacity. Before these data are initialized, `slice` is `nil`, so for `slice`, `map`

|

||

and `channel`, `make` initializes their underlying data and assigns some suitable values.

|

||

|

||

`make` returns non-zero values.

|

||

|

||

The following picture shows how `new` and `make` are different.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Figure 2.5 Underlying memory allocation of make and new

|

||

|

||

Zero-value does not mean empty value. It's the value that variables default to in most cases. Here is a list of some zero-values.

|

||

```Go

|

||

int 0

|

||

int8 0

|

||

int32 0

|

||

int64 0

|

||

uint 0x0

|

||

rune 0 // the actual type of rune is int32

|

||

byte 0x0 // the actual type of byte is uint8

|

||

float32 0 // length is 4 byte

|

||

float64 0 //length is 8 byte

|

||

bool false

|

||

string ""

|

||

```

|

||

## Links

|

||

|

||

- [Directory](preface.md)

|

||

- Previous section: ["Hello, Go"](02.1.md)

|

||

- Next section: [Control statements and functions](02.3.md)

|